NEW YORK — Diagnosis of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA), the most common type of cicatricial alopecia in Black women, continues to be overlooked, with a variety of factors, including atypical symptoms, leading to delayed diagnosis and inappropriate treatment.

Susan C. Taylor, M.D.

CCCAs are typically characterized by important descriptive characteristics that are apparent in their name, but they are more easily overlooked than widely recognized, says Susan C. Taylor, MD, professor of dermatology and vice chair for diversity, equity, and inclusion at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

In a scoping review of 281 cases of CCCA described in 99 recently published studies, Taylor and colleagues cautioned that while approximately 70% of patients had the classic symptom of centrifugally expanding central scalp hair loss, almost one-third did not.

Atypical CCCA is classified into two main types:

“There were two distinct types of atypical presentation,” she said in a presentation at the 2024 Skin of Color Update. In neither case was hair loss on the top of the head a prominent feature.

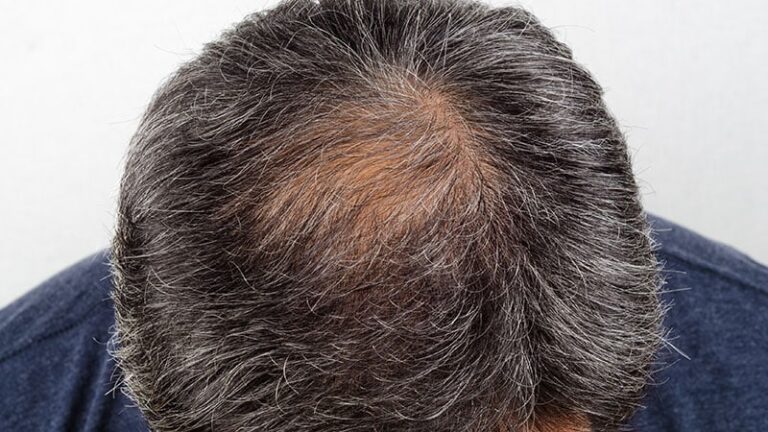

In some cases, the hair loss is most characteristically patchy and may affect the occipital, vertex, or frontal areas. In other cases, the hair loss most closely resembles male pattern baldness and, in the case presented by Taylor, resembled secondary syphilis. Hair destruction was noted in many patients, with vertex involvement being common.

Taylor cautioned clinicians to be aware of the limitations of traditional CCCA nomenclature, saying failure to consider CCCA in black women presenting with alopecia can lead to misdiagnosis, delayed diagnosis, and inappropriate treatment.

“CCCA is a progressive disease, so we don’t want to miss or delay the diagnosis. We want to start treatment as soon as possible,” she said.

She said the same principle applies to black men, whose risk for CCCA is underestimated. For those considering CCCA in men, it’s also important to consider atypical symptoms, according to Taylor, an author who recently published a review of all CCCA cases in men in the University of Pennsylvania database.

“That’s the bottom line: If you’re considering male pattern baldness in black male patients, you should consider CCCA,” she said.

Dermatological diagnosis is useful for both men and women

In both men and women, suspected CCCA should be evaluated with dermatoscopy and scalp biopsy. The main features on dermatoscopy are a honeycomb-like pigmented network and a white ring around the hair follicle, measuring 0.3-0.5 mm in diameter and sometimes accompanied by small white dots of similar size. White spots appearing as a “starry sky” pattern also support the diagnosis of CCCA on dermatoscopy.

Amy McMichael, MD

Amy McMichael, MD, professor of dermatology at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, also strongly advocates for the use of objective tests such as dermatoscopy and hair testing. She also spoke about CCCA at the 2024 Skin of Color Update and emphasized the importance of considering atypical CCCA.

“You need to think about it more holistically,” said McMichael, who recommended immediate testing of the back of the scalp if CCCA is suspected. Rather than simply preventing further hair loss, McMichael said the goal is to allow hair follicles to recover and function normally after the inflammation from CCCA has been controlled.

McMichael says that while CCCA was once thought to be caused by chemical relaxers and other products used in hair styling, it is now more often seen as caused by a genetic predisposition. In fact, while McMichael advises CCCA patients to talk to other relatives about their genetic risk, he no longer advises all patients to immediately stop using chemical relaxers.

The cause of the hair care product is unknown.

McMichael points out that there is conflicting evidence linking the risk of CCCA to the use of hair care products and does not focus on this as the primary etiology. Instead, he emphasizes treatments that can rapidly control inflammation, which he believes is a prerequisite for achieving durable remission.

When evaluating the scalp, she strongly recommends assessing the degree and severity of inflammation as the first step in planning treatment. “I try to really push patients who are in the inflammatory stage,” she says. She individualizes treatment based on whether the patient can tolerate aggressive treatment, but would consider topical and intralesional steroids and oral antibiotics to treat pustular disease.

Once the inflammation is under control, I educate my patients on the various options they can consider to reduce inflammation, including topical minoxidil or, in difficult cases, plasma-reduced protein (PRP), laser therapy, or surgery. In all cases, these approaches should be introduced after the inflammation has been controlled.

But CCCA must be recognized as a chronic condition, McMichael said. She cautioned that topical treatments and PRP are best viewed as maintenance interventions. Patients often stop treatment once they see hair regrowth, which she said is a mistake. Patients should be discouraged, even if the treatment is expensive or inconvenient, or because their CCCA has been cured.

“If you recommend this treatment to your patients, they will lose their hair again if they don’t continue the treatment,” McMichael warned.

Taylor, president-elect of the American Academy of Dermatology, reported financial ties to more than 25 pharmaceutical and cosmetic companies. McMichael reported financial ties to AbbVie, Almirall, Arcutys, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CeraVe, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, LEO Pharma, L’Oreal, Perage, Pfizer, Procter & Gamble, Revian, Sanofi-Regeneron, Sun Pharma, and UCB.

Ted Bosworth is a medical journalist based in New York City.